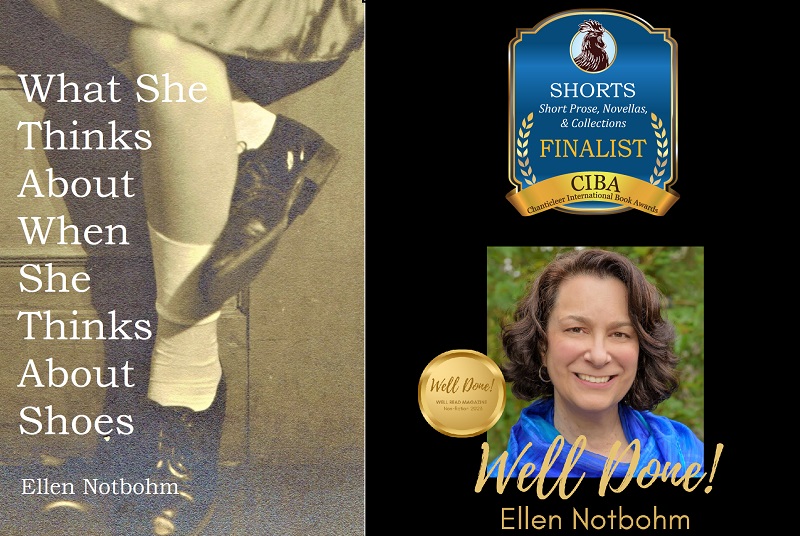

What She Thinks About When She Thinks About Shoes is an exploration of how my mother’s dementia impacted our relationship, ultimately exemplified by a pair of hauntingly, unforgivably ugly shoes. A Chanticleer International Awards finalist for short prose, it’s published in the April 2023 issue of Well Read literary magazine.

Excerpt:

WHAT SHE THINKS ABOUT WHEN SHE THINKS ABOUT SHOES

My mother wouldn’t have liked me looking in her closet. No one knows what goes on behind closed doors, she often declared, an always-effective conversation ender. For all the years of my childhood, the door to the bedroom she shared with my father sported a sign reading “No one under 21 allowed,” and neither me nor my brothers breached the invisible force field at that door unless expressly invited. She wouldn’t have wanted me to see the still-life behind the closed doors of her closet, the nature morte, laid out there in dusty relief when the old hollow core door creaked open along its pocked track. But although she is only a few miles away, she will never return to this house, this room, this closet. The day had come for me to open those doors. No one else could.

And there were the shoes. Shoes upon shoes. Upon shoes.

The more favored pairs stood upright on the arched prongs of a metal rack shoved against the back wall. The rest of them rose from the floor in a Yertle the Turtle-style jumble, the newer and hardier ones on top, the crumbling, fading, silently useless ones on the bottom. And all of them, eerily turtlelike in their sameness.

Let’s talk about shoes, back in the day. Back in the day before everyone said, back in the day.

Back in the day, children like us didn’t have wardrobes of shoes. We got one pair at the start of the school year.

I didn’t always get to choose that one pair, or even get to have an opinion about them. I didn’t think much about shoes at all. I put ’em on, I walked around in ’em.

The one-pair thing made sense in my family, given my father’s comfortable but not extravagant income, and given the need to buy shoes for three children’s feet, growing like mushrooms and sometimes smelling like them. I didn’t think about how my shoes were in intimate contact with my body for most of my waking hours. How shoes are visible as all get-out. How they might make noises, groaning and whimpering and drawing the humiliating kind of attention a child dreads. How they affected where I could go and how I’d feel getting there.

I never had reason to think that awful consequences could befall me for having no choice, no voice about shoes until one year, a certain pair of Mom-chosen shoes became millstones. Shackles. Cement suckerfish.

Somewhere in my middle childhood years, my mother decided that my one pair of school shoes would be clay-and-brick-colored two-tone saddle shoes. I can still taste the revulsion in my mouth when, with those boxcars on my feet in Leeds Shoe Store, she made that decision. I gag on their sheer ugliness, their leaden weight, their utter lack of girl-ness. I was a girl child of the 1960s. I wanted to look and feel like a girl, a girl who wore Mary Janes, go-go boots, t-straps with teardrop cut-outs, red canvas sneakers with blinding white laces. I knew as surely as I’d known anything in my short life that the saddle shoes would rob me of that girl-ness. The shoes knew it too. They grew unapologetically heavier on my feet by the second. They saddled me, all right. In every physical and metaphorical sense I could not yet put words to.

Why didn’t I protest? Mom? I hate these shoes. I’ll be unhappy every minute I’m in them. They make me feel ugly. Please don’t do this. Why didn’t I point to her own caramel-colored sleek but sturdy ladies’ loafers and ask, can’t I at least have something like those instead? I couldn’t find my voice. My mother was a kind and practical woman. I didn’t argue with her, ever. I knew that to her, the saddle shoes were a triumph of practicality.

Durable! Rain-resistant! Roomy! I’m sure she saw nothing unkind in choosing such shoes.

But I must tell you. They weren’t shoes.

They were clodhoppers.

They weighed me down, not just by their actual tonnage and rigidity. What my mother couldn’t see was how those shoes added more tremor to my already shaky self-image. I was large and tall, and those shoes added yet more mass, their bulbous toe box hovering over my already adult-sized feet.

Look at my elementary school class pictures. That’s me in the center back row, a head taller than everyone else, shoulders slumped, one cheek turned away, trying to make myself look smaller. No 1960s elementary school class photographer ever thought that perhaps that big girl didn’t want to be the peak-of-the-pyramid focal point in every class photo, perhaps he could put her at the end of a row, one row down from the top, or even seated in the front row. It wasn’t a day and age where a young girl would feel dauntless pride of self for towering over every kid in the class, and the teacher, and sometimes the photographer.

Every day I wore those clodhoppers felt like I was serving a sentence for a wrong I couldn’t fathom.

I never forgot those shoes. But I can’t remember how I got rid of them. Did I finally ’fess to my mother how viscerally I hated them? Did I make a case for how they hurt my feet (well, they did, right?). Did I accidentally-on-purpose cause them to come to some irreparable harm? Did I grit my teeth until I outgrew them?

Somehow that desperately desired severance happened, but the scar remained: never again in my life would I wear a pair of shoes that I so organically hated, that hated me back with a perversity some inanimate objects seem to wield.

Half a century later, the memory of them came back to me, still leaden, but with overwhelming irony.

.

Continue reading the story here.

Leave A Comment