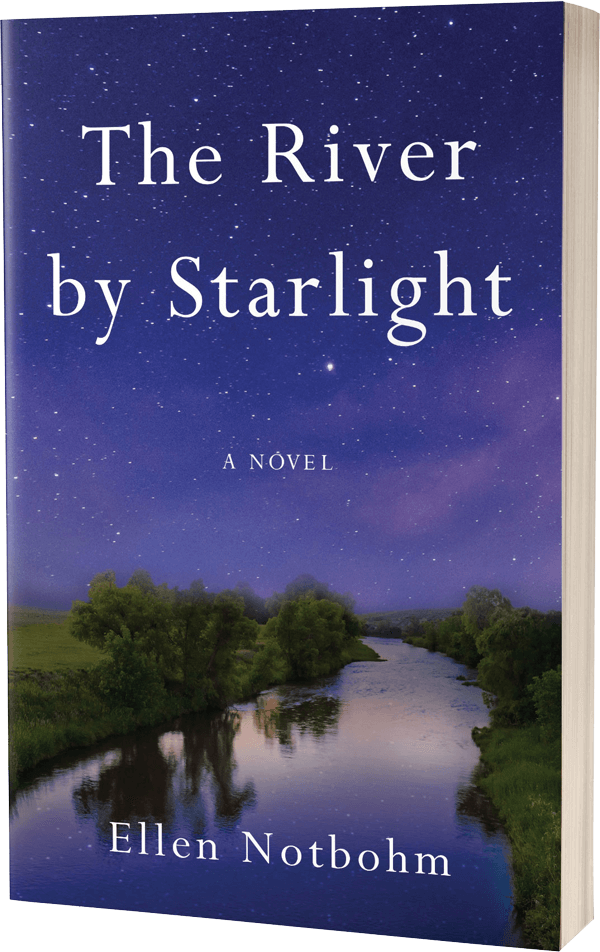

Chapter Four

An excerpt from The River by Starlight

The conversation with Cal Rushton wandered around Adam’s head for days, trying to find its way out. Why he would even consider leaving the store, and by extension the plans for his own store, made no sense.

On an unseasonably warm April day, when no one needed club ties or half hose or Dakota-style Stetson hats, he stared at the door, which hadn’t opened once since he had unlocked it and walked through himself, and it finally registered. It wasn’t the farming from which he had desperately wanted to distance himself. It was his father, the fruitlessness of part-time farming, and the knowing that working for his father meant he would never accumulate enough money to have something of his own.

When he called on Reuben Dunbarton, the man seemed to be expecting him. “Just in time,” he boomed, chestnut eyes bobbing beneath shafts of chestnut hair. Adam asked the salary he was off ering. Dunbarton named a fair number, and Adam, somehow needing to give himself a last out, said he had a higher number in mind—say, half again more. Dunbarton laughed, clapped him on the shoulder, and said, “Go to it, lad.”

In the months since, running the business of the Dunbarton farm from a desk and a phone in a niche by the back door of the farmhouse has brought Adam deep and startling contentment. Coaxing living products from the dark beneath the soil thrills him in a primeval way he doesn’t try to understand.

It’s been some weeks since he last came by Cal’s place. This late of a September afternoon, deep shade veils the riverside path beside the swaying rows of wheat. From his wagon, Adam notes the new chicken corral. He pulls his horse up, scanning the fi elds for the rangy Cal’s distinctive gait. A woman emerges on the path, her tread so light that he isn’t aware of her until she’s almost upon him. She resembles Cal, although more than a foot shorter. And while Cal’s step carries the impression of perpetual inebriation, this woman’s stride is all business. A blue dragonfly hovers over her shoulder like an escort, zooming away when she waves it off and stops a cautious distance from Adam.

He jumps down and tips his hat. “You must be Cal’s sister. I’m Adam Fielding.”

“Charmed, I’m sure.” She seems about to offer her hand but instead slides it into a fold of her skirt. “Analiese Rushton. Cal speaks fondly of you. The ‘taskmaster,’ yes?” Unlike Cal, she delivers the handle with a straight face.

“He’s fond of telling me that I can’t fire him; slaves have to be sold.”

She nods knowingly. “What can I do for you? Cal had to go to Havre. He accidentally plugged a gopher hole with his foot. The doctor wanted it examined with an X-ray machine.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. It sounds painful.” And costly. He’s concerned for his friend, surely. But now his crew is down a man, and there are no extras to be had this time of year.

“It was. You won’t soon see a fatter salami.”

Adam holds the reins of his champagne palomino loosely at his side. “Cal said he couldn’t afford a threshing crew and aimed to winnow the crop by hand with an old Confederate flag. I couldn’t tell if he was joking, and when he didn’t show for work today, I thought perhaps he wasn’t.”

“True, we’re going to winnow by hand. But I’ll be coming up with a less wieldy fan than a Confederate flag.”

“No need, Miss Rushton. I came to tell Cal that I’ve arranged for our threshing crew to do it. If he’s hobbled, he won’t be able to refuse, will he?”

“How very kind of you. And thanks for coming out. I’m trying to convince him to put in a telephone. To save important folk”—this too she declares with a poker face—“the trip.”

“Obliged.” Adam touches the brim of his hat again. The telephone at Dunbarton’s is indeed where he’s headed. He faces an afternoon of calling across the countryside trying to scare up an extra hand for the threshing.

An explosion of leaves and snapping branches erupts from the trees along the river, and a blur of fur hurtles toward the chicken corral. Wolf! Adam registers like a shot from the rifle he doesn’t have with him today. A bold daytime offensive in full view of people means the animal is wild with hunger. Adam gropes under the seat of the wagon, hoping he’s wrong about the rifle, astounded that the Rushton girl shows no concern, barely glancing at the animal. She’s apparently too new here to recognize what she should fear.

The blur of fur sails over the side of the corral. The squawking fowl seem to scold rather than flee, the scene almost comical as the wolf catches a hind foot on the coop’s fencing and crashes into its center, careening bum over teakettle to regain its footing and vaulting the opposite side, paying no heed to dozens of captive meals. It shoots past Adam, between the legs of his palomino. The horse shrieks and bucks, catching the wolf in the rear quarter and sending it into the road, where it lands in a heap for a second time. The Rushton girl, who must be mad, trots toward it, tossing her head and clucking something that sounds like, “Oh, Dio.” Before she can come close enough for the mauling Adam is sure will follow, the wolf leaps to its feet and throws itself into a whirling dervish, mistaking its own tail for an object of pursuit.

Adam grabs for the harness of his spooked horse, but it twists to get away and the cart fishtails, knocking his legs out from under him. The reins whiplash the air and wrap themselves around Adam’s middle like a frightened child. His back smacks the shaft on the way down, snatching the wind from his lungs. Voiceless, laid out flat, with a wolf on the loose and his friend’s sister directly in its path, he’s about to see a woman be eaten alive. Like a bad dime novel. If only it were.

But the Rushton girl bellows, “Blasted varmint” and “Stay there, Mr. Fielding.” She marches right up to the animal and backs it into a ditch on the side of the road. The beast hunkers down, feral eyes fixed on her, tail swishing while she commands, “Duo, you moronic menace. You stay your sorry carcass right there until I tell you otherwise!”

Adam, pulling himself up, sees now that the animal is no wolf, but a mongrel dog of incomparable homeliness. Its eyes don’t match, one brown and one gray with a rusty ring and cocked outward. His mangy coat furrows across his spine; he doesn’t fit in his own skin. Inches of pink tongue dangle from his muzzle, too long for his mouth. Miss Rushton glowers at the mutt, starts to turn to Adam. The mutt skulks a tentative step out of the ditch.

Cal’s sister whirls on him, snapping, “Try it!” and the hound tries no more. Bloodshot eyes blink meekly over the rim of the ditch.

“Sawdust where most critters have brains,” she grouses. “Mr. Fielding!” She hurries across the road. “Are you hurt?”

Adam regains his footing, but his palomino is still stamping and prancing. Adam grasps the bridle’s cheekpieces and pulls the horse’s head to his level. Whispering in Michif—“Tapitow . . . steady . . .”—he strokes the palomino’s neck, then brings his face near the nose, breathing in and out along with the animal, calming both of them. He pulls a pouch of oats from a pocket. The feel of the horse’s velvet muzzle in his hand diffuses some of Adam’s own agitation. When the horse quiets, Adam lets its head up for a cautious look around.

He probes the sore area of his lower back. It’s throbbing, but not as dire as he feared. The Rushton girl asks again if he’s hurt. He’s not about to tell her that the wound to his pride stings worse than the one to his flesh. His gaze goes to the cur in the ditch. “Duo?”

Miss Rushton rolls her eyes. “Cal’s idea of a joke. ‘Dog of Unknown Origin.’ You haven’t met? He came with the property.” She throws a barbed frown at the ditch. The dog lays his head on the ground, looking sorry and resigned. The girl shrugs. “They love each other.”

“What in tarnation was he chasing?”

“Who knows? Dog dreams? I truly am sorry, Mr. Fielding. Can I get you some coffee?”

He’s trying to work a thumb into loosening a knot of leather in the tangle of reins. “No, I don’t want any damn coffee,” he mutters.

“Something stronger?” she asks, unruffled.

For the first time, he eyes her closely. She’s not much to look at. Absurdly small. She disappeared a minute ago when she darted behind the horse to grab the other rein, momentarily confusing him. Maybe five foot tall on tiptoe, he judges. A child-sized woman who melts in and out of view.

Her face seems unfinished, as if the artist started work on it and grew bored, packed up the brushes and chisels and paint pots and moved on to more inspiring material. From a distance he might have called her plain, but this close she radiates an uncanny energy. Her hands, too large for the rest of her body, glow two shades darker than the wheat behind her, as do her arms, up to the elbow because—oh, woman after his own heart!—her sleeves are rolled up. Most unlady-like. Most attractive. His eye drifts to her lightweight skirt. With her back to the sun, he can see the silhouette of a slender thigh. Sweet jumpin’ joey, the woman isn’t wearing undergarments? He forces his attention to her face. He’s not seen black eyes like those since his horse-trading days. Dark and bright at once, that magnetic pull, slivers of white at corners, and— Yes, he could use a drink.

“I wouldn’t mind.” Then, testing her, though he’s not sure why, he adds, “Would you join me?”

“Sure.” She starts toward the house.

He can’t believe it. “You’re going to drink with me?”

“Put you under the table, big fella.”

Adam isn’t a particularly big fella, and she’s downright puny. He can’t tell if she’s being insolent, if she’s calling his bluff, or if she’s just damn interesting. Does it matter?

“Where do you get the stuff?”

“Homemade, what else?”

“You have a still?”

“I have a grain barrel and a Ford radiator. Does your horse have a name, Mr. Fielding?”

“Tipsy.”

She laughs, an enchanting chuckle from such a plain face, the breezy retort of a butterfly flirting with a falcon. “Better put Tipsy in the pasture. You look thirsty.”

Before he turns the palomino out, he scouts the pasture, wading into the grass halfway to the woods. A flash of gray tail in the trees tells Adam that Duo is in retreat.

At the open door of the shack, he knocks politely.

Two chairs huddle under a plank table where Annie has set out an amber bottle and two glasses. Light enters the cabin through two windows, one tall and narrow over the sink, facing the river, the other square across the front of the shack with a long view up the road. Rich blue damask framing the front window suggests a tablecloth has been conscripted as draperies. She waves him in.

“Would you like ice? I have plenty in the cellar.”

“Straight up, thanks. No ice.”

“I meant for your back.”

He lowers himself into the chair without comment. He’ll have to pay attention if he’s to stay a step ahead of her. Why can’t he take his eyes off her?

“No? Suit yourself.” She uncaps the bottle, and the glug of whiskey splashing against glass fills his ears. “Bottoms up, big fella.”

“And the fourth deadly sin is sloth, according to my father, the Reverend Fielding.” When he tips the bottle against his glass, nothing comes out, and his watch has slipped a gear and advanced two hours in the space of a few minutes. It doesn’t usually take him this long to impress a girl out of her bloomers, and this one may not even be wearing any. Not that he’s trying to. Not her. Not his type. “In Latin, acedia—how about that?”

“This isn’t sloth,” she tells him, somehow stone sober. “It’s convalescence.”

“Convalescence?”

“You were hurting and now you’re not, am I right?” She gets up without waiting for his answer. “You look as if you have taken root in that chair. Are you staying for supper?”

Is that some sort of convoluted invitation? She’s an impudent girl, even if she is his friend’s sister. From gracious to audacious and back again in the same minute. And she’s wrong about the chair. He could get up if he wanted to. But what the heck, why not play along a while more? Sure, he’ll stay.

The food clears his head enough to recover some decorum. “Splendid supper, Miss Rushton.” Another reason to envy Cal: being permitted to eat without enduring Fiona Dunbarton’s incantation of grace in three languages. “Do you have a special name for this?”

Annie nods solemnly. “I call it chicken. The round green things, I call them peas.”

“Charming, aren’t you?” So much for decorum. “And where did the lady learn to drink like that?”

She settles back in her chair. “The red slices, I call them tomatoes.”

“Cal?” Adam cocks a cupped hand to his lips, tipping an invisible glass.

“I’m not going to tell you. I don’t know you well enough.”

Adam, not a man who laughs readily, can barely keep his lips together. A smoke would be the thing right about now. She won’t object; she’s no temperance lady. Reaching inside his jacket for his pouch of Prince Albert, he asks, “Would you mind if I were to have a smoke, ma’am?”

“If you do, I’ll assume you’re on fire and douse you with the bucket I keep under the sink for such occasions.” She indicates with a finger over her shoulder. “I can’t promise that Duo hasn’t sampled it.”

He holds a hand up. “No offense intended, Miss Rushton.

May I call you Analiese?”

“Could I stop you?”

“Do you want to?”

“I couldn’t care less what you call me. I may or may not answer to it. Whatever you come up with, I’ve been called worse, and by my own relations.”

Is that a dare? Baiting him to press her for more, so she can dodge again? He must remember to ask Cal if this is her nature, or peculiar to the situation.

“You too? At least your name isn’t a profanity with a vowel in front of it. My uncle used to swear when he was exasperated with me: ‘Aaaaa-damn!’ Then I would remind him of the biblical origin of the name.”

“Ah, the sacred and the profane, conjoined. I can see how that would be exasperating. Courtesy of Reverend Fielding, I take it?”

“His father. I’m named for my grandfather.”

She props her elbows on the table, her hands together under her chin. “This grandfather, does he, too, consider you to be profanity preceded by a vowel?”

“No. I was a boy when he passed, but the old gent liked me. He and my mother. As for the rest of the gospel-breathing, Bible-thumping Fielding clan . . .”

His voice trails off. Too much work to finish the thought. He can feel the girl searching the blankness of his face, looking for a chink in the surface that will tell her something. She won’t find one. “The rest of the gospel-breathing, Bible-thumping Fielding clan,” she finishes for him, “deem that such a well-reared, industrious, good-looking gent should have settled down by now. Don’t tell me—firstborn, right?” He doesn’t answer. “Roaming the prairie, back and forth over the border a thousand times. Heaven forbid, consorting with the natives your father tries to convert.”

Bold little wench, isn’t she? “I didn’t say—”

“You didn’t have to.” She gets up to clear the table. “If that has earned you the reputation of a profanity with a vowel in front of it”—she raises the empty whiskey bottle—“the hell with ’em.”

He tips back on two legs of his chair. How does she know these things? Four guesses and she’s batting a thousand. “What about you, what’s your story? Cal doesn’t talk about his family.”

She turns her back and hefts a pot of water onto the stove. Into the pot she scrapes the chicken bones and potato leavings, an onion still in its papery skin, the tomato cores, some carrot tops. He half expects her to toss in a stone. She’s avoiding and provoking him, and that’s a conundrum. With women, the decision to avoid or provoke has always been his. The food has soaked up some of the sway of her moonshine but left a gap he must close to regain his accustomed upper hand.

He hooks his thumbs into his belt and feels the watch in his pocket tick against his hip. She grinds pepper into the pot and chops a handful of parsley. She seems to have forgotten his presence. He draws in a deeper breath, as if he could pull her head around.

Just when he thinks she’s sidestepped his question entirely, she dries her hands on her apron and returns to the table. Her words have a minuet recital quality. “Cal became a firstborn by default when our brother died, seven years before I was born. In our mother’s eyes, those were shoes no one could fill. Her very words. Cal left home about twenty years ago. Our sister married. She’s still in Iowa. Our other brother took over the farm when our parents died. I’m . . . lastborn.” She turns to the window, speaking to the river. “I was five when Cal left, and it broke my heart. He rarely came home. His last visit, our ma was particularly hard on me, and Cal told her that ours was ‘the very house where glad comes to die.’ He left the next day. That was eight years ago, and I didn’t see him again until I stepped off the train here. But I hold that memory dear—the rare occasion when someone shocked our mother into silence.” She tugs her apron off and tosses it on the table. “Is that a good enough story for you, Mr. Fielding?”

“No,” he says, more sharply than he intended. She gives him the slightest of shrugs. “You left eight years out. But I bet I’d have to put a ring on that finger to get the rest of it, eh?”

There, he’s thrown down a gauntlet. If she’s anything like Cal, she won’t be able to refuse picking it up.

“Aren’t you the brash one.” She slings a dish towel over her shoulder and crosses her arms, one hand beating a tom-tom rhythm against her elbow. “A bet assumes that you have something I want, Mr. Fielding. Tricky business, assuming. How drunk are you? For all you know, the rest of my story includes Cal teaching me bare-knuckles boxing and a nasty left uppercut.”

Her look could melt the stripe from a skunk. Now he does laugh. She is, oh yes, she is a worthy sparring partner. “Ladyfriend, I’m left-handed. I could stop your uppercut cold. Might even break your sturdy little arm.”

“My, you are terrifying. After I finish washing up the dishes here, I’ll consider fainting.”

“Analiese—if I may call you that—you are something.”

“You are something too, Mr. Fielding.”

“Adam.”

He might be drunk, but he can still count. Eight long beats and she doesn’t blink. On the ninth beat, he wins.

“Adam.”